The Aesop store in Covent Garden is a cool oasis off a bustling street in the heart of London. I caught whiffs of bergamot, mandarin and perhaps Tonia from the threshold and the silence engulfed me as soon as the door silently swung shut behind me. My social media over the past years had made me aware of the brand’s existence and bougie affiliations. The closest encounter I had had with it, culturally at least, had been a year previous when it sponsored the photography competition for the London Review of Books and The Paris Review. The prize was, I believe, a year’s supply of skincare products from the company. Living in Lahore, my highest hope was to be afforded the opportunity to even enter the contest. Winning these products was hardly the point because, knowing Pakistan’s customs and postal services, the only outcome I was sure of was these products getting “lost” on their way to me. Getting ahold of my physical copies of any magazine I subscribed to was a task that required constantly emailing to inform them that I had not received my copies after weeks of waiting, and feeling the shame accompanying these emails, in case the recipient thought I was lying to procure extra copies. No subscription lasted more than one cycle for me, and having run the gamut of the Literary Review, the New Yorker and the London Review of Books, I finally stuck to exclusively online subscriptions.

The terms and conditions of the photography competition, advertised in the LRB, said nothing about excluding international participants and so I plotted with my friend Maheen about my ideas for the photographs I wanted to take. She was game to participate we decided to put it into execution the next Friday after work. I brought my camera to the office because we had decided to conduct the shoot at the Lahore Museum and the Railway Station, which were near both our offices. I had brought a copy of my LRB because that was the one condition: the photography had to include a copy of either the LRB or The Paris Review. By the time we left our government offices on that Friday evening, all the other government buildings had also closed, the Museum being one of them. Not ones to be discouraged, we made the most of what we could see from the pavement outside. Maheen posed in front of the grills encircling the Museum while holding the magazine open and scanning it. We then proceeded to Kim’s gun, named after the main character from the eponymous novel by Rudyard Kipling. The colonial contours of this photography project for a British magazine was lost on neither of us. We, however, were only out to enjoy ourselves and so we went on to disturb the pigeons flocking around the cannon, eating the grain that people spread there every day as a form of charity.

My dreams of taking photographs with birds flying everywhere were finally fulfilled. This was not an unusual or unique photograph by any means: I had seen many photos of school classmates at the start of a new school term when they returned from a visit to London, where they were photographed feeding pigeons in Trafalgar Square, or from Umrah in Saudi Arabia where the square in front of the Masjid-e-Haram in the 90s was crowded with pigeons, before they too were replaced by the skyscrapers now towering over everything. I had, however, never taken that sort of photograph before, and neither had I been its subject. I managed to have both this day, which was very satisfactory.

Even though the competition required only one photograph to be submitted, Maheen and I were not about to let such a clause stop us from having more fun. We then headed to the Railway Station, partly because we had not seen it for more than 20 years. In the early and mid-90s, when we were small children, taking the train as far as Rawalpindi at least was very common, but as one corruption scandal followed another and the trains began visibly falling apart, the middle classes chose other means of transport to travel around Pakistan. Nobody wanted to waste precious vacation days waiting 24 hours for a train that wasn’t just late but sometimes never showed up at all or broke down on the way to its destination. Voyeurs that we were, we wanted to satisfy our curiosity and partake (from a safe distance) of the glamour of trains. Despite their undesirability as reliable means of transportation, trains are glamorous. Crossing various parts of Lahore, especially Cavalry Grounds in the Lahore Cantonment before the flyover was built, has required stopping at the phaatak (the railway crossing signal and gate), waiting for the train to pass. As a child (and honestly, even as an adult), I always hoped that our car would be at the front of this queue when that powerful, rumbling steel monster roared past. Its sound and fury as it rattles everything in its vicinity and vibrates through your bones are unmatched.

My plan was to photograph my friend reading the magazine, the only still figure in the whole place, as everybody else passed by in ghostly variations of movement. I needed to use a very low shutter speed to accomplish what I envisioned and Maheen assured me that standing still as a statue while I did this was the easiest task. I set up my tripod because even though she could hold still for that long, my trembling hands would definitely blur the photo if I did it freehand. The camera was barely set up when two women and a man in uniforms appeared at our elbows, demanding that we show authorization for our project. We were startled but not completely surprised, having become uncomfortable familiar with the workings of government officials and the power trips even the lowest ranked had in bullying people they perceived as ordinary powerless civilians. Maheen calmly held up the magazine and told me to take my shot. The officials moved threateningly closer to my beloved camera, starting to actually reach out and raising their voices, all overlapping as they screeched about “security”, “permission” and the “SP” (superintendent of police). I warned them not to lay a finger on my equipment or me, trying to keep my tone neutral even as my blood started to boil at their rudeness. We knew that there was no rule stopping us from taking photographs in a public place where everybody had their phones out to take photos anyway. We asked to see their senior officer ourselves and clear it with him, but this left them flabbergasted and scrambling for excuses for why that just wasn’t possible. They told us that the senior official was in meetings for the rest of the day. The train, meanwhile, was about to depart, which would make our project futile because: a)- the locomotive was a pretty significant part of the proposed photograph; and b)- the darting figures of other people too would disappear from the frame.

We took our photographs, responding to the officials’ shrieks by calmly assuring us that we would wait to meet the SP if they wanted and that if he asked, we would delete the photographs. We also gave them our official visiting cards, headed by the Government of Pakistan logo, which left them deflated further and they turned away, mumbling that it was fine and we should just take our photos and leave.

Once we’d finished a task that took barely 5 minutes, we ran out of the station to our waiting car, and drove to the government officers’ club near Maheen’s house where we ordered club sandwiches and giggled while scrolling through the photographs we’d taken that day. As the sun set, lighting up the leaves of the gulmohar trees outside the windows, I couldn’t help basking in the warmth of one of my most affirming friendships.

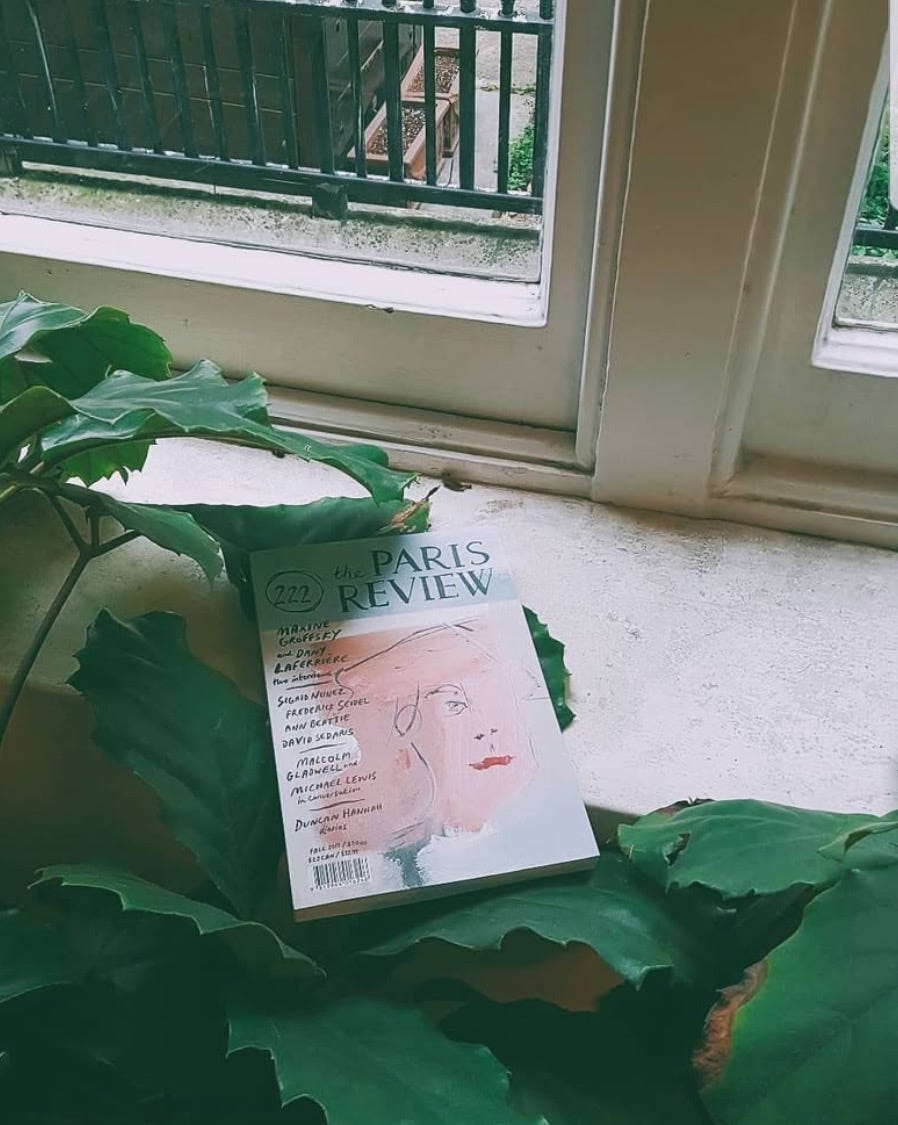

I recalled all this when I stepped into that tiny, peaceful store in London. I was wandering around and at the back of the store, next to a window looking onto the church, was a pile of identical books. The legend bore the name “The Paris Review”. Since Aesop sponsored the magazine, they also stocked copies of it. Next to a giant potted monstera, the pale pink and blue covers tempted visitors to wash their hands at the stone sink with bougie skincare products, take a seat on the window sill and flip open a copy. I wonder if anybody dared to ever do that. I merely took some surreptitious photographs in the beautiful light streaming in through the windows while the staff was busy attending to another customer, and then stepped back out into the bustling street in the heart of London.

Note: I wrote this piece at the end of April 2025, two weeks before the threat of war between Pakistan and India materialized. Over the past few days, with my heart in my mouth, unable to swallow, constantly refreshing news sites and frantically switching amongst any and all reliable sources of information I could find, this piece slipped to the back of my mind. All I’ve been able to think of this entire past week has been home, my family, friends, the places that have formed me and all my memories. I have procrastinated a lot about posting my life on the internet and recently, all I’ve wanted is for my memories to be preserved. So this piece is now part of my attempt to do just that. I send this out with a lot of love for the person in this piece, who was part of our lighthearted adventure, and all the other people I love and miss right now. May we all be safe always.

beautiful beautiful, as always!! keep writing ❤️

This was beautiful to read— like I was there myself!